Article 1: Understanding financial markets and investing

Introduction

This is our first article publishing on this platform. We also intend to publish, on a bi-weekly basis, a series of modules to allow the individual investor to understand financial markets, ‘risk and return’ and how to make informed investment decisions. This will be based on a MSc Investment Management I created, but will be delivered in a simple, non-quantitative way to allow an individual who has not studied investments at university to understand the key concepts and how to read the news and understand how investment markets are impacted. Investing for our future is one of the most important things we do in our lives and I hope this series helps you better understand the large and complex subject of investing.

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

What is investing?

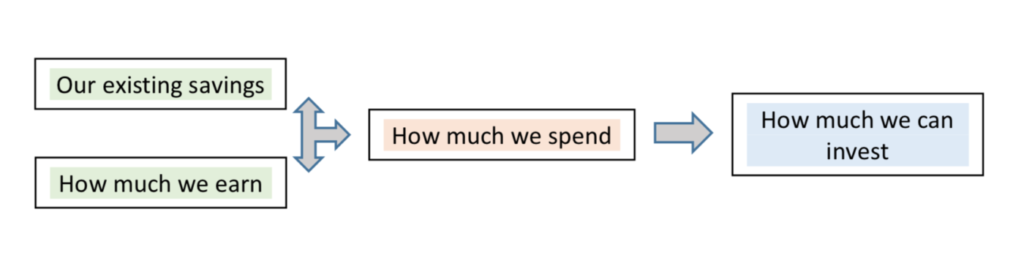

If we have money now, either surplus earnings or previous savings, we have two choices. One, we can spend it on items like food, clothing, a car, etc. This is called consumption (or spending). If we choose not to spend all the money we have currently, we can save or invest some of it for the future. This is called investing and what these modules will focus on. (‘Savings’ and ‘investing’ are just used to represent different ways to invest; we use ‘saving’ when we put our money in a bank deposit and use ‘investing’ when we buy an equity in the stock market.) Right away, we can see there is a strong connection between how much we spend and how much we can invest. Therefore, a disciplined and structured approach to investing must be done in conjunction with a budget for how much we earn and how much we spend.

The investment decision starts with:

What are my investment alternatives or choices?

It is normal practice to place an investment into one of four categories:

- Cash – usually short-term deposits at a bank or, perhaps, money market fund

- Bonds – longer term debt instruments, either issued by a government or a company, thatpromises to repay the principal after a certain time (say, ten years) and to pay a periodic (oftenannual) coupon or fixed rate of interest

- Equities – perpetual (no maturity date) securities that may pay a dividend depending on theprofitability of the company

These three asset classes are referred to as traditional investment assets and have been around for a long time. In recent years, investors have invested in other assets, some of which are new and some of which used to be considered consumption assets (real estate in particular).

4. Alternative assets – real estate, commodities, Bitcoin, paintings, and many others.

The most important distinction to first understand is between that of debt (cash and bonds) and equity. Here are the two critical variables that make debt different from equity:

- a payment on debt (coupon) or interest on a deposit is a legal promise to pay whereas the dividend on an equity is a discretionary payment that management may choose to pay, if it has adequate profits

- bonds or deposits almost always have a repayment or maturity date (and a legal promise to repay at that date) whereas equity securities are perpetual instruments; you can only recover your investment by selling the shares in the market at whatever the market price is then

Alternative assets are quite diverse and so I will only comment on one, real estate. Real estate has some similarities to equity; it has no guaranteed annual income and you can only recover your investment by selling the asset into the market at whatever price it is then selling at. Studies in other markets show real similarities between equity markets and real estate, both in terms of per annum returns and volatility.

We group similar assets into categories (‘bonds’, ‘equities’, etc.) as they share similar levels of risk and return, a critical concept we will now discuss.

‘Risk’ and ‘Return’ – two concepts you must understand

Investment strategy has two components:

- Investment objectives: risk and return

- Investment constraints: liquidity, time horizon, regulations, tax and unique constraints

In this first article, I want to focus on the understanding of risk and return, as they are fundamental concepts you must be able to understand to be able to invest wisely.

In finance, the definition of risk is uncertainty, and the future is, by definition, uncertain. But, we have to plan in our lives and make forecasts of the future. Let us look at examples of risk and with reference to the terms ‘actual return’, ‘promised return’ and ‘expected return’.

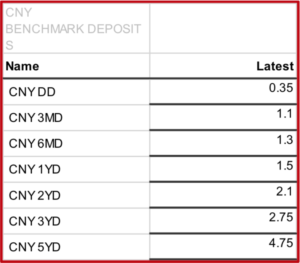

First, let us look at the example of a one-year deposit at a bank in China.

Here we see a selection of interest rates quoted by a large bank in China on 5 October 2018 with terms varying from one day to five year. The bank is offering to pay a rate of interest of 1.50% for a one-year deposit. If you deposited 100.00 today the bank promises to pay you back 101.50 in one year’s time. You do not expect a large bank in China to default on its deposits and so you think the actual return you get in one year will be the same as the promised return – you believe there is a low risk you will not get this amount.

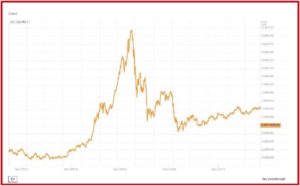

Now, let us look at an example of investing in the stock market (Shanghai Stock Exchange) As equities do not have any maturity date or value, what you can sell at stock at in one year’s time is simply what you forecast the value of the stock to be – there is no promised return or selling value.

On 11 June 2014 the value of the SSE was 2,046, on 11 June 2015 it was 5,121 and on 13 June 2016 it was 2,833. If I had invested for one year in 2014, I would have made a return of +150%! But if I had invested for one year in 2015, I would have made a loss of 45%. Clearly, trying to forecast what your actual return will be in the future in the stock market is very difficult – it has a high level of risk.

If we had also looked at bonds, we would have seen that the expected return and risk were both somewhat in the middle of cash (deposits) and equities.

If one investment is expected to provide a higher expected return than another, the one with the higher expected return will also have a higher level of risk – conversely, there will also be a greater chance of losing more with the investment that has a higher expected return. The bank deposit above paid a very low rate of return, but it had a very low level, almost zero, of risk. The investment in the equity market could have made you a huge profit – or a huge loss.

Risk and diversification

Diversification is a very powerful tool for investing but is difficult to explain without using maths, but I will try. Let us use equity markets as an illustration.

Say you have some discretionary savings (savings you can afford to lose) and are prepared to accept the risks of investing in equities. You have identified five stocks that are mature companies and have been listed for a long time and so there is much historical data on each of the five stocks. Over the last tenyears, you calculate that the per annum return for each of the stocks was similar, about 10% per annum, on average. You have also seen the risk (as measured by annual volatility) has been about 20% per year. They all look quite similar and so you decide to invest in the stock that you prefer.

But then you realise that the five companies are in different industries. Even though their ten-year averages of per annum return and risk were the same, they were not the same in each individual year. We say the stocks are not perfectly correlated. So, instead of putting 100 into just one stock, it might be a better investment to put 20 into each of the five stocks. Here, you would expect to earn around 10% in total per annum, but it is likely that your risk (volatility) is less than 20% – and that is a superior outcome. Diversification is a complex but very powerful concept and can be very valuable in investing.

“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”.

8 October 2018