Introduction

This is our fourth Article and looks at the ‘human side’ of investing: behavioral finance.

What is Behavioral Finance?

To understand finance, we need to have a basic understanding of economic theory, which forms the basis for finance. Classical economics is based on many assumptions but one important one is the assumption of ‘efficient markets’. Here are just a couple of the underlying assumptions:

One can immediately see that the above two assumptions of an efficient market are not realistic. In reality, today, educators use the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) as a starting point to analyze markets and by dropping these restrictive assumptions they can better understand the actual operation of any real market. There are two general ways to deviate analysis from the EMH.

Behavioral finance is all about relaxing the second assumption.

“Behavioral finance…in essence, simply recognises that human beings, individually and collectively, behave as humans (having psychological qualities) and not as gas molecules (having only mass and velocity).” (Source: Frankfurter & McGoun – Ideology and the Theory of Financial Economics Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation 1999)

The human mind is an incredibly complex thing and so studying psychology is also a very complex area of study with all sorts of difficulties in forming general and consistent theories.

“Behavioral Finance merges psychology and economics. Some say the result is bad psychology and bad economics”. (Source: Richard Taffler, February 2007)

But at the end of the day, the price of a security is just whatever price is agreed by two human beings in a negotiation (or by them through some technology). Thus, despite its complexities, we need to understand human behavior if we are to understand how markets work.

Later in this series of Columns, we will look at various issues and cases about behavioral finance indepth. The purpose here is to give an overview of the topic and highlight some key themes. I will refer to information taught by James Hand, formerly CIO of Investec Asset Management in London and who used to teach on my MSc Investment Management in London. He was one of the leading investors in London and internationally in the field of behavioral finance and its applications for investing.

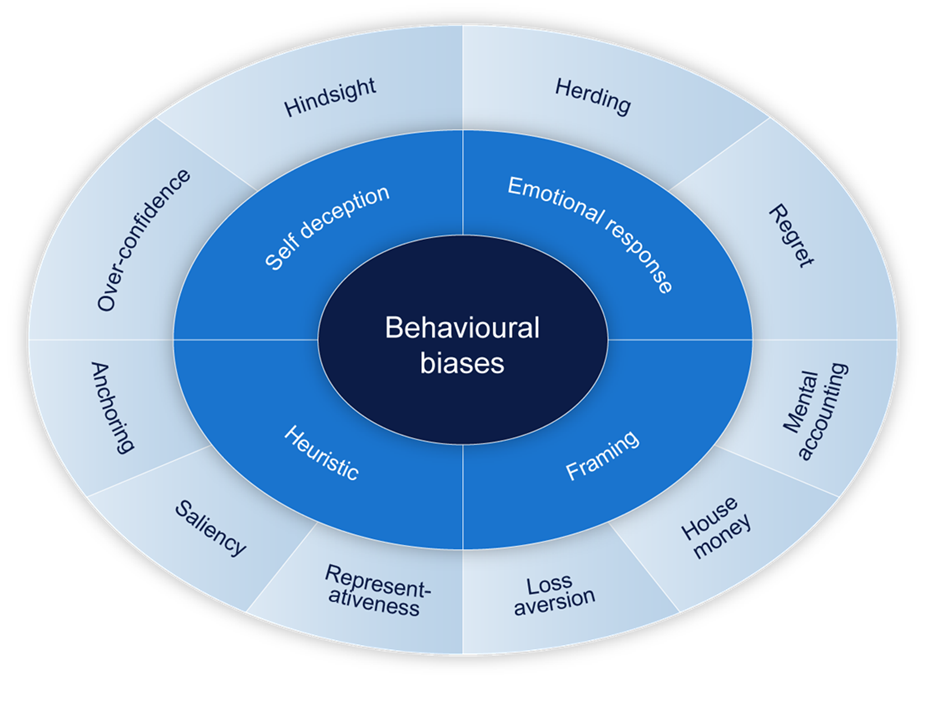

Understanding how some of these behavioral biases, like overconfidence, might lead to bad decisions is probably obvious. However, I want to briefly discuss two: heuristics and herding.

Heuristic (definition): is a form of discovery but one that almost always involves a simplification of the decision process. In England we sometimes talk about ‘rules of thumb’; simple rules for making decisions in complex situations. The problem is, like in investing, some situations are complex and simple rules do not always bring us to making the correct decision. Heuristics help us avoid ‘information processing limitations’ (i.e. lots of work) and time processing limitations (i.e. lots of time). A lot of people use heuristics and this leads them to make inappropriate investment decisions.

A market of bubbles

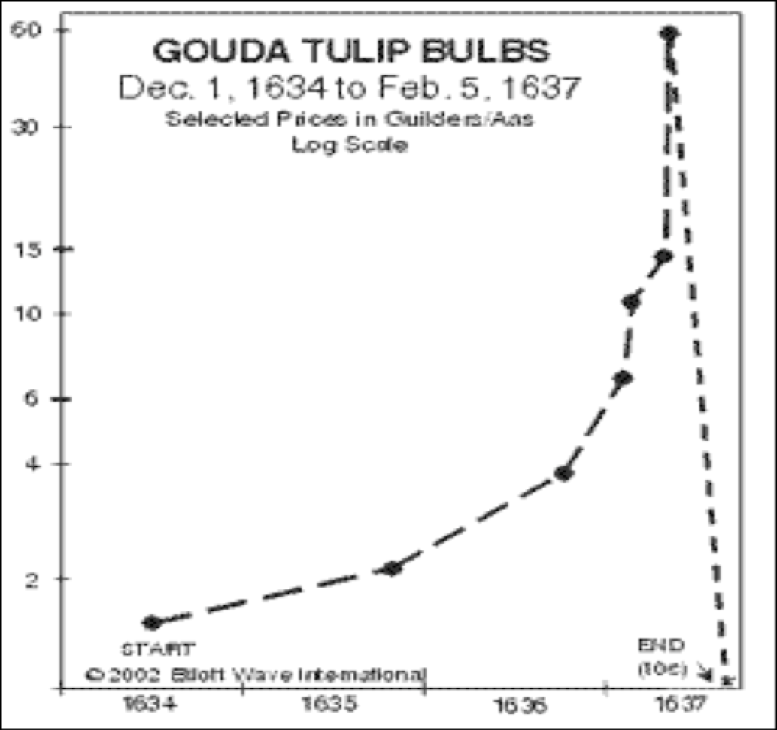

Our world economy is full of economic and financial ‘bubbles’. I used to teach a course related to behavioral finance just about the ‘History of Market Bubbles’. To give a historical perspective, we first looked at ‘tulip mania’ in The Netherlands in the 1700’s.

Tulip mania (Dutch: tulpenmanie) was a period in the Dutch Golden Age during which contract prices for some bulbs of the recently introduced and fashionable tulip reached extraordinarily high levels and then dramatically collapsed in February 1637. It is generally considered the first recorded speculative bubble. (Source: Wikipedia).

Initially, a tulip bulb was priced around 1 guilder in late December 1634. By February 1637, that price had almost reached 60 (a gain of 6,000%). But, by May 1637, the price collapsed back down to below 1(a loss of 99%). That sort of price movement was very extreme, but we have seen similar bubbles arise in other markets and real estate and stock markets are two asset classes where we have seen many large bubbles, which always lead to crashes.

Looking at tulip mania, the ‘tech market crash’ of the NASDAQ in March 2000, the real estate crash in America of 2008 and maybe the bike-sharing crash in China of 2018, we see some common behavioral errors made by investors. Clearly, people are driving valuations to levels that don’t make sense. Hence, education and an understanding of historical returns provide an important benchmark for investors to judge when things are becoming of extreme and ridiculous value. However, these sort of extreme price bubbles can only occur when a lot of money (meaning, frequently, a lot of investors) invests in the asset – what we call ‘herding’. Herding is what happens when people make investment decisions because ‘everyone else is doing it’; but without doing proper investment analysis to see if it makes sense. To protect your investments, objective and independent assessment is required.

Agents and Incentives – investor beware

As people, we rely on ‘specialists’ to give us advice and/or service for complex matters we have to deal with in life. For medical assessment we go to a doctor. For legal advice we go to a lawyer. To buy a house we might commission a real estate agent. We spend a lot of time and money being guided by specialists in areas where we don’t feel we have enough knowledge, experience or connections to work alone. And we hope these people have our best interests in mind when working for us.

But these ‘agents’ are people just like us who are looking to earn a living. Are our objectives in investing the same as the Financial Advisor (FA) we rely on? If not, we may have a problem. In paying an agent there are two examples of compensation: one is paying just a monthly fixed fee to give us advice. The other is to pay a commission based on, for example, how much money we invest. In financial markets and investing, we find a lot of FA’s work based on a commission. So, if we invest 100,000 with them, they earn a commission of 5,000. But if we decide not to invest with them, they don’t earn anything.

Investing is fundamentally different to buying goods. When you purchase, say, furniture for your home it is a ‘one-off’ transaction; you are not going to return the furniture in ten years and get your money back. But investing is a long-term relationship, not a one-off sale and you do hope to get your money back with a return in the future. What further complicates the investment relationship is that almost always the FA is selling you investments of ‘third parties’ – i.e. not an entity where the FA will have the responsibility to pay you back. Compensation by commissions is what we say creates a ‘moral hazard’ in investment advice. You, as investor, want the best investment for your personal needs. The FA wants to earn the biggest commission as quickly as possible. ‘Mis-selling’ is one of the biggest problems we have in financial markets and all around the world. This is equally true in China where commissions drive so much of the financial transactions that take place.

This commission issue is partially, also, the fault of the investor; frequently they are hesitant to pay ‘consulting fees’. They want to believe they are getting something tangible for the money they pay. But, in theory, paying a fixed consulting fee to your FA is likely to get you the best objective advice for your investments as the FA has no financial incentive to ‘sell you something’. You should, at least, ask your FA to advise you how they are compensated so that you can determine how much pressure they have to sell you investment products. FA – devil or angel?

*****

Understanding how people behave, alone or collectively, is essential in investing. Don’t just blindly ‘follow the herd’.

John D. Evans, CFA (author) has over 24 years’ experience in the international capital markets working with issuers of securities and investors around the world. He has designed and taught Master’s programmes in investment management at universities in the UK and China. He was most recently Professor of Investment Management at XJTLU in Suzhou. He now manages SEIML, a consultancy to early-stage companies in China.

Jina Zhu (translator) did her Master’s in Economics in France and is fluent in Mandarin, English and French. She also works at SEIML supporting early-stage companies grow and raise capital in China.

16 February 2019

Benny曾在中国金融市场工作,聚焦于固定收益、货币和资产负债管理。 他目前是宁波一家中型私募基金管理公司量利资本的副总裁。 公司的策略包括各种类型的固定收益投资组合管理和可转换债券投资组合管理。 此外,Benny 还为证券公司母基金、企业投资者和高净值个人等专业投资者提供金融投资服务。

Benny 还一直活跃在证券业务的商业领域,管理客户业务发展战略、营销计划和路演,并为中小型银行和其他金融机构开发和提供金融市场培训计划。

Benny 精通普通话、英语和日语。

自 2014 年春从法国攻读研究生回到中国以来,Jina一直致力于电商领域及其在金融、娱乐和汽车行业的应用。 她是一位多功能人才,能说流利的普通话、英语和法语。

Jina 是 SEIML 在外国客户和中国行政机构之间的主要关系经理,曾多次负责与在中国运营的国际公司和管理人员打交道。 因此,她负责管理公司与客户的所有业务流程外包(BPO)活动。

她拥有经济学研究生学位,并完成了特许金融分析师协会(CFA Institute)颁发的投资基础证书,因此具备协助外国公司进行中国市场研究的知识,包括对潜在客户、供应商或其他第三方进行审查。 她在使用中国社交媒体方面也颇有心得。

Jina 精通普通话、英语和法语。

John 职业生涯的前 24 年是在投资银行度过的,先是在多伦多,后来短暂去了纽约和伦敦。 他曾为欧洲、中东和非洲地区的大型基金提供债务资本市场(DCM)、股权资本市场(ECM) 和战略投资咨询。

2004 年,他转入学术界,在英国和中国的大学设计并开设了投资管理硕士课程。 在英国大学就读期间,他还创建并管理着欧洲一家规模较大的金融专业培训机构(该机构是培训公司的合资伙伴)。

2016 年,John 重返行业,与初创企业以及各种平台和生态体系合作,为这些处于早期和中期阶段的公司提供支持。 起初,他在上海地区开展这项业务,但后于 2024 年迁至香港,以便在东南亚地区建立 SEIML 的足迹。 John 还是香港创始人协会(FI)生态体系的董事和 创始人协会东盟金融科技加速器的项目总监。