Introduction

This is our seventh Article and looks at how to value a company. The company model of financial analysis we propose can actually be used for any investment, deposit, bond or common share. But, in these articles, we are focusing on equity investments and so will tailor our analysis to the valuation of a company’s common equity.

Financial analysis is a critical component of investing and so this will be the ‘first in a mini-series’ of five articles on the subject. Today, we provide the general framework and in the following four articles we will focus more deeply into the components of the analysis.

Financial analysis: a top-down approach

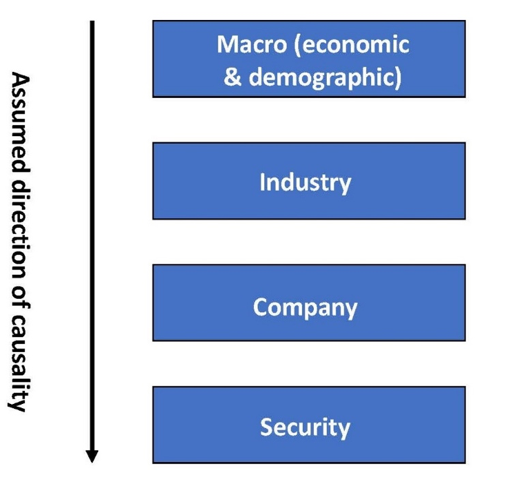

Our model for valuing a common share is based on a fundamental, four-stage, top-down process.

The rationale for this ‘top-down’ approach is that large forces drive smaller forces. So, the economy (global macro) has a large impact on an industry. The industry prospects will determine the company prospects, on average. In the company there may be many different securities issued and so we must value the particular security we are investing in (common shares in our example).

In our articles, we assume all readers are investing in China (global investors can choose which country to invest in). Thus, our focus will be on the bottom three levels. However, it is worth noting that China’s GDP growth is the highest of any large industrial economy and so provides a good base for all industries.

But, let us look at all components, including Global Macro so that we can understand all the interactions.

Global Macro

When I worked for an investment bank in London, I used to speak with many large investment funds throughout Europe and the Middle East. Almost any fund that was allowed to invest globally would follow this top-down approach to investing. The starting point was always how much money to allocate to a particular country, before looking at industries and individual companies.

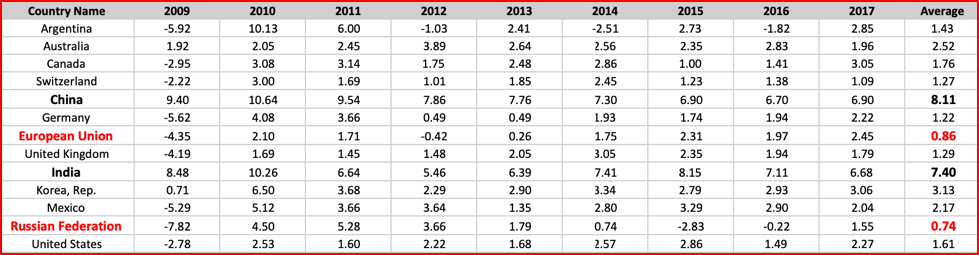

There are many variables in deciding on which country to invest in. But, one we have discussed before, relates to ‘growth’; growth of a company, growth of an industry or growth of an economy (global macro). There are many ways to measure the growth of an economy, but growth in GDP is likely the most popular. We can see below that GDP growth vary greatly, even among the world’s largest industrialized economies.

We can see above that the GDP growth rates (over the last decade) have been much higher in China (8.11%) and India (7.40%) than any other large economy. At the other end of the spectrum, we see growth rates have been very low in the European Union (0.86%) and Russian Federation (0.74%). There will, of course, be good and bad investments in any of the above countries. But, on average, we would expect to find more good investments in high growth regions than in low growth areas; growth trickles down from the economy to industry to company and growth in revenue leads to growth in profits.

There are a few caveats to this focus on GDP growth. First, these are historical numbers and what we really want to know is what growth rates are expected in the future. This will require some careful analysis of the country to see if recent historical growth rates are expected to continue for long into the future. One important but often overlooked factor in farecasting country GDP growth rates is demographics.

Demographics: a long-term driver of an economy

Demographics is the study of human life. Two important variables are:

The study of demographics is important for many reasons. It is also important to study in economics. We assume there is a positive correlation between population size and economic potential (growth of GDP). It is not a perfect +1.0 correlation; lack of education, poverty, corruption, etc. can prevent large countries from reaching their economic potential. However, it remains an important variable in country analysis (global macro).

Above, we said that growth in the economy is something we need to forecast for the future. If the population of a country is ‘young’, then there will be a much larger number of people working and contributing to economic growth. If a population is ‘old’, then there will be relatively fewer people working and more in retirement. Despite China’s very high, current GDP growth rate, its previous onechild policy suggests that the average age in the country is steadily rising and this will put pressure on future economic growth. Demographics are driven by physical relationships and are hard to change in the short term and forecasts of population tend to be more accurate than forecasts of economics, which are more driven by political decisions.

“The problems of an ageing and declining population are by no means confined to old-age provision. Nearly all areas of the economy and society are set to feel substantial effects. The spectrum ranges from fundamental changes in the labour market, with corresponding effects on the relative prices of capital and labour and on national growth potential, to the effects on international capital flows and hence exchange rates, and extends to changes in sector structures…Furthermore, population development affects the financial markets, partly via the age structure and hence savings patterns, while the financial markets play a role in shaping the demographic trend via income generated there.”

Source: Deutsche Bank Research, ‘The demographic challenge.’, September 2002

Industry analysis

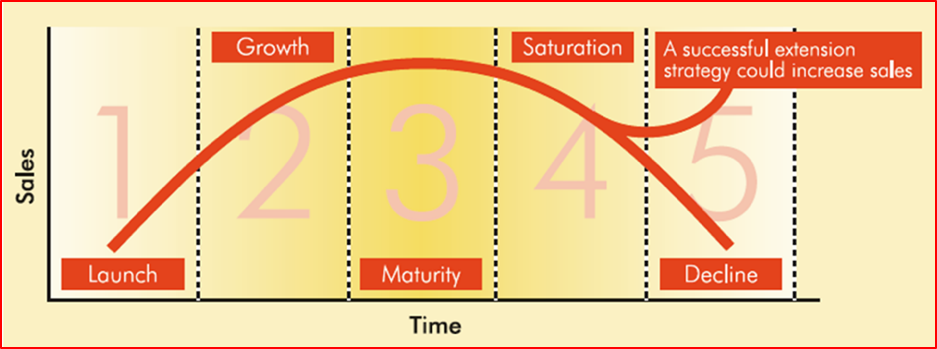

The ‘search for growth’ is as much a focus at the industry level as it is at the macro-economy wide level. Again, higher growth in revenue (sales in the below graphic) will lead, on average, to higher profits. We introduced this graphic in a previous article, but it is worth reviewing again here.

Quoting from Article 6: Private Equity:

“Successful new companies will be Growth companies, but as they get larger their growth will slow down. Growth is an important input into equity value and so companies growing quickly (but only if they are profitable) will see there share price grow more quickly than slow-growth companies.

But, over time and as a company gets larger, its growth will slow down due to increased competition and other factors. The company moves into the Maturity phase and its share price may be high but not increasing much anymore. Some companies eventually become unprofitable and Decline because new technology comes along and disrupts their business model.”

Some equity investment fund managers whole approach is to try and find ‘growth stocks’. But, also referring back to Article 6, we stated how younger companies (where the growth typically is) have less of a track record, often are smaller with fewer sources of capital and so are more risky than larger and more mature companies.

Never forget the golden rule of finance: higher growth can produce higher expected return. But, higher expected return means higher risk.

China provides a classic example of a country going through industrial change. As a consequence, some mature industries (i.e. steel production) will go into a state of decline while a variety of new industries (i.e. healthcare) appear poised for higher long-term growth. There is much research underway to help the investing public determine what industries are likely to show higher growth in the coming years. One piece of government policy is the Made in China 2025 government decree of what industries it will be providing greater support to. The ten highlighted industries are:

Of course, if everyone knows these are the industries of the future then everyone may start buying into these industries pushing the share prices up and making them not attractive as investments. So, after we identify the growth industries, we must then do detailed analysis on the companies in those industries to find the good investments.

Company analysis

The company analysis is sub-divided into two categories. The first is the quantitative/financial analysis. The sole purpose of this exercise is to try and forecast the future cash flow of the company (and risks associated with that forecast) to allow us to discount these future cash flows to value the company. The next three articles (8: income statement, 9: cashflow statement & 10: balance sheet) will be dedicated to explaining this financial analysis and so we won’t address it directly here.

The second category is the qualitative analysis. Not all of the critical issues can be quantified and reported in a company’s accounts; it can be argued that the most important of all – the ability of management – does not show up anywhere, directly.

As time passes, the ‘intangibles’ become more important. When the country was dominated by lower-level manufacturing then the value of property, real estate and equipment was an important part of the analysis. But in today’s ‘knowledge economy’, it is ideas and new techniques that make a new company a successful ‘disruptor’. Though patents may be one indication of a company’s value, it is really the ideas and vision of the founders – and a solid operational platform – that makes a company valuable. This is making the assessment of these new industries more difficult to do.

Common Share analysis (share valuation)

The last step in our analysis is to come to our opinion on what the common share is worth in money today. This value is given many names in finance books that largely mean the same thing: fair value, net present value, intrinsic value, etc. – but not market value. Market value, or what we can actually buy and sell the stock at, is what we compare to our fair value to decide whether we want to buy the share or not. If we value a share at 10.00 but we can buy it in the market at 8.00, then we view that as a good investment, we say the stock is ‘cheap’. But if we value the share at 10.00 and it can only be purchased at a price of 12.00, then it is not a good investment, we say the stock is ‘expensive’. So, in making an investment our financial analysis must give us a very precise value of what we think the share is worth.

The theoretically correct way to value a share is by discounting all of its future cash flows back to the present to determine its net present value (or fair value, intrinsic value, etc.). We may employ other valuation ratios or parameters as a cross-check to see if our fair value is inline with market guidelines of similar companies. But, valuation by discounted cash flow (DCF) is the model that is the basis for our share valuation. This will be the subject of Article 11 and we will describe this model in greater detail in that article.

To close out this article, I will mention a few other topics that are part of the financial analysis process.

Time-series analysis

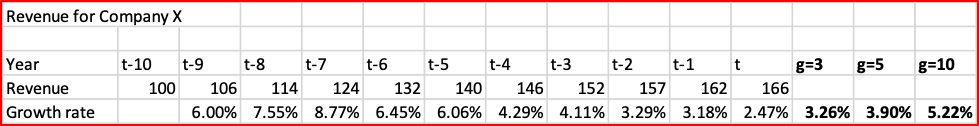

So many of our attempts to forecast the future are based on extrapolating historical trends and then applying a bit of judgement. As we will see in Article 11, it is common to make a detailed forecast for five years into the future and then a less detailed forecast for the period (the residual) thereafter. But so much of this will be based on recent history, ten years being a common time period used. Let us take a look at a hypothetical company and its revenue for the last ten years. From that we will calculate the growth rate of revenue for the last 10 years, 5 years and 3 years. The numbers are below.

We can see in the above that the shorter the recent period used the lower the growth rate. This is consistent with our industry life cycle that says over time a company’s growth rate will decline. So, taking the longest period of time of historical results may not be the best period to extrapolate and forecast into the future. Trends change and by looking at various historical periods it will require us to make judgements about what growth rates to use in our forecast.

Peer Group Analysis

Some people are not confident in their ability to use DCF in their decision making. An alternative approach is to select industries that have above average potential and then look simply to invest in the best performing companies in that industry. To do this sort of peer group comparison, we perform financial analysis on all target companies and find out which ones show the best company performance by analyzing various ratios related to profitability, leverage, cash flow, liquidity and a host of other performance indicators. These ratios will also be explained in articles, 8, 9 & 10.

Concluding remarks

Financial analysis is a complex subject that requires a systematic approach to the analysis of data and markets. The top-down, four stage model is a common approach taken by equity analysis, though there are other models as well. This article provides an overview of the process and interactions between the four levels. We also discussed the first two components, country and industry analysis. The next four articles will look at the company financial analysis (articles 8, 9 & 10) and close off with discounted cash flow analysis (article 11).

Caveat: in more recent years many global investors drop the country analysis (as they can hedge the currency) and focus on global industries. However, due to capital controls, Chinese investors are restricted in what they can invest outside the country. Thus, our model is still very useful for domestic investors in China.

*****

Having a systematic approach to financial analysis and investing is important, it ensures consistency in analysis and decision making. There is a great amount of information in the market but taking the approach in this article (and the following four articles) gives you a way to manage all this information and synthesize it in an effective way. Yes, financial analysis can be difficult and time-consuming, but there are no easy ways to make good decisions in complex situations. It requires a sound method, time and experience.

John D. Evans, CFA (author) has over 24 years’ experience in the international capital markets working with issuers of securities and investors around the world. He has designed and taught Master’s programmes in investment management at universities in the UK and China. He was most recently Professor of Investment Management at XJTLU in Suzhou. He now manages SEIML, a consultancy to early-stage companies in China.

Jina Zhu (translator) did her Master’s in Economics in France and is fluent in Mandarin, English and French. She also works at SEIML supporting early-stage companies grow and raise capital in China.

15 April 2019

If you have thought of operating a business in Asia, or already have one, then do not hesitate to contact us to see how we might be able to help you set up, raise private capital, and manage your company’s local administration.

©2025

Snowdonia Evans Investment Management Limited (SEIML)

Benny has worked in the financial markets of China with an emphasis on fixed income, currency and asset-liability management. He is currently Vice President of Longly Capital, a medium-sized, Ningbo-based private fund management company. The firm’s strategies include various types of fixed income portfolio management and convertible bond portfolio management. In addition, Benny offers financial investment services to professional investors such as Fund of Funds (FoF) of securities companies, enterprise investors and high net worth (HNW) individuals.

Benny has also been active on the commercial side of the securities business managing client business development strategies, marketing programmes and roadshows and developing and delivering financial markets training programmes for small and medium-sized banks and other financial institutions.

Benny is fluent in Mandarin, English and Japanese.

Since returning from graduate studies in France to China in spring of 2014, Jina has been continually working in the field of e-commerce and its applications to the financial, entertainment and automotive industries. She is a multi-functional talent and fluent in Mandarin, English and French.

Jina is SEIML’s key relationship manager between foreign clients and the Chinese administrative authorities and has held many responsibilities dealing with international companies and executives operating in China. As a result, she manages all of the company’s Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) activities with clients

With her graduate degree in economics and completion of the Investment Foundations certificate from CFA Institute, she has the knowledge to assist foreign companies in China market research, including reviews of potential customers, suppliers or other third parties. She is also quite savvy in the use of Chinese social media.

Jina is fluent in Mandarin, English and French.

John spent the first 24 years of his career in investment banking, first in Toronto, briefly in New York and then London. He was involved in DCM, ECM and strategic investment advisory to large funds in EMEA.

In 2004 he moved into academia and designed and ran MSc programs in investment management at universities in the UK and China. He also created and managed one of the larger financial professional training organizations in Europe while at the UK university (that was a JV partner in the training firm).

In 2016, John returned to industry to work with start-ups and various platforms and eco systems to support these early and middle stage companies. Initially he pursued this venture in the Shanghai region but then moved to Hong Kong in 2024 to build SEIML’s footprint in Southeast Asia. John is also a Director of the Hong Kong Founder Institute (FI) eco system and Program Director for the FI ASEAN Fintech accelerator.